These mental roadblocks often present themselves in familiar refrains:

These objections are understandable, but often shortsighted. The truth is, you don’t need to be a professional writer. You need to be a professional with insight: someone who has seen, solved, and led through challenges worth learning from.

The BIG Secret…

You don’t have to be a writer to get your ideas into the body of knowledge. As a matter of fact, some publishing insiders estimate that upwards of 60 percent of bestsellers are actually ghostwritten. Therefore, the research and writing can be supported by expert collaborators. In other words, let a professional writer put their expertise to work for your ideas or storytelling.

What matters is your willingness to own your narrative. Savvy leaders never win by themselves, so don’t think that writing your book means holing up by yourself for a year, hovering over the keyboard, and slowly driving yourself bonkers.

Teams make winning possible, so crafting your book with the best available resources should be your goal.

The greatest risk is not writing. Executives who stay silent lose control of their story. They allow competitors, markets, or algorithms to define their leadership brand. Worse, they miss the opportunity to document their unique thinking in a way that benefits their organization and inspires their team.

“Leaders often underestimate how much their story can inspire others. That’s not ego—it’s impact.”

—Kurt Merriweather, Vice President of Global Marketing, Workplace Options, and co-author, The Inclusive Leadership Handbook

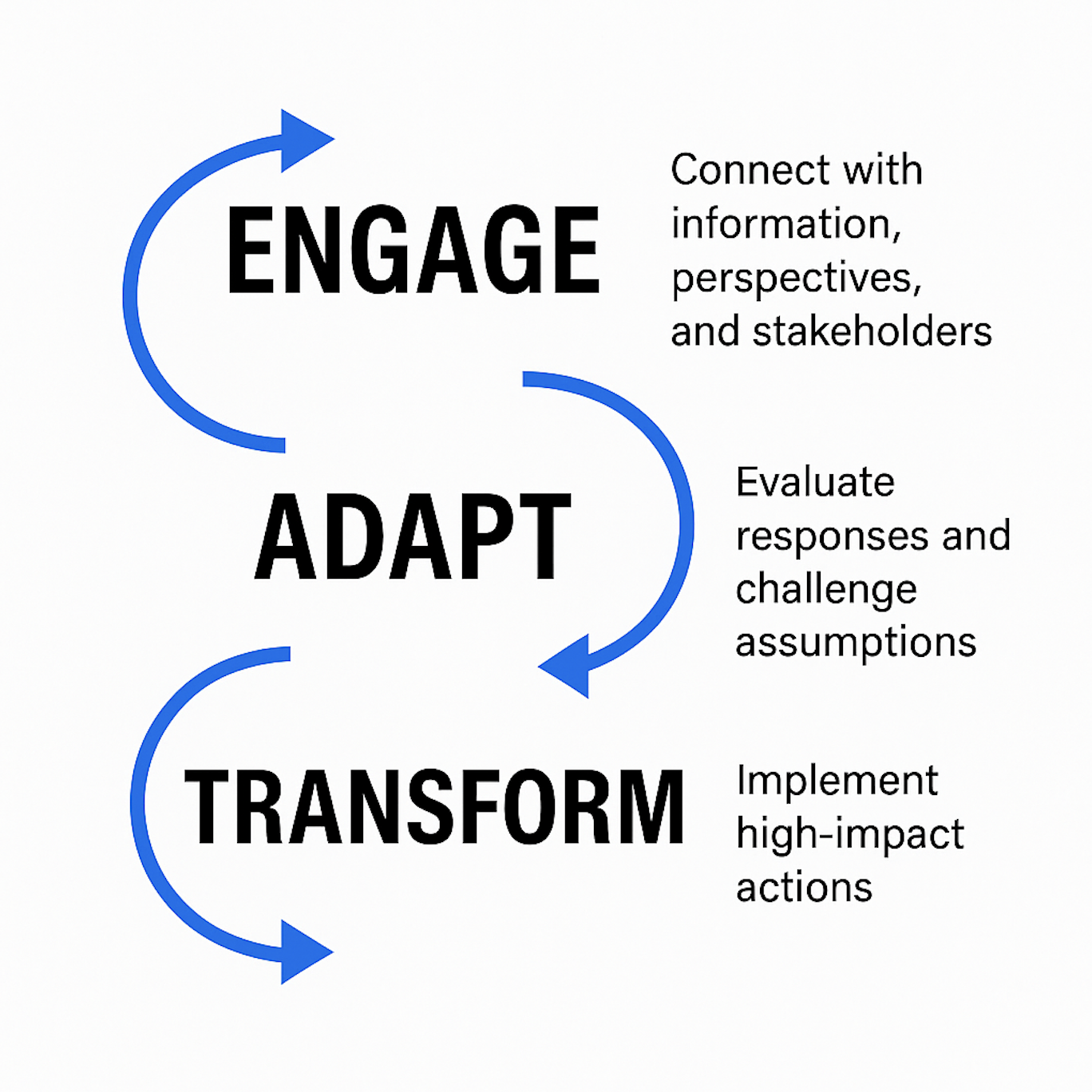

Many people view writing a book as a personal win. That’s fine, since everyone will have different reasons for crafting their book. Here’s another way to look at it, though. Think of your book as a strategic tool for clarity, alignment, and growth.

Your book forces you to ask:

What do I really believe?

What do I want to be known for?

How do I want to be remembered?

Answering those questions? That’s where great leadership begins.

For more information about writing your book, ghostwriting, or executive-level thought leadership, visit the team at ExecBrand Authority or email me directly: bob@bobbatchelor.com.