Every author’s journey begins the same way: with a blank page and a glimmer of an idea. For aspiring nonfiction writers—and anyone who feels the tug of a story inside them—the hardest part is often starting. Whether you are a pop culture aficionado, would-be biographer, or someone drawn to capturing history, there is no perfect moment to begin your book.

You just start.

My own writing journey began in a high school newsroom, writing columns and dreaming of the bylines I might someday see in glossy magazines. I came of age in a college town (Slippery Rock, PA, home of Slippery Rock University) where professors and ideas swirled around me. Writing felt aspirational. A cherished teacher—Martha Campbell—rewarded my hard work with a sports column featuring my work: “Batchelor’s Bench.” I loved writing that column and holding our small high school newspaper in my hands.

As a college student, I sent essays to publications that were way out of my league. The rejections piled up, but the process enabled me to slowly build confidence with each reply—published or not. Every so often, there would be a kind note or something that looked like more than a stamped “rejection.” Those were glorious days!

About a decade later, by the time I wrote The 1900s (Greenwood, 2002), I approached it from a researcher’s mindset. I had yet to fully develop my narrative voice, let alone the courage to let it rise on the page. The 1900s, though, served as a foundation: meticulous research, structural discipline, and an unwavering commitment to learning during the writing process.

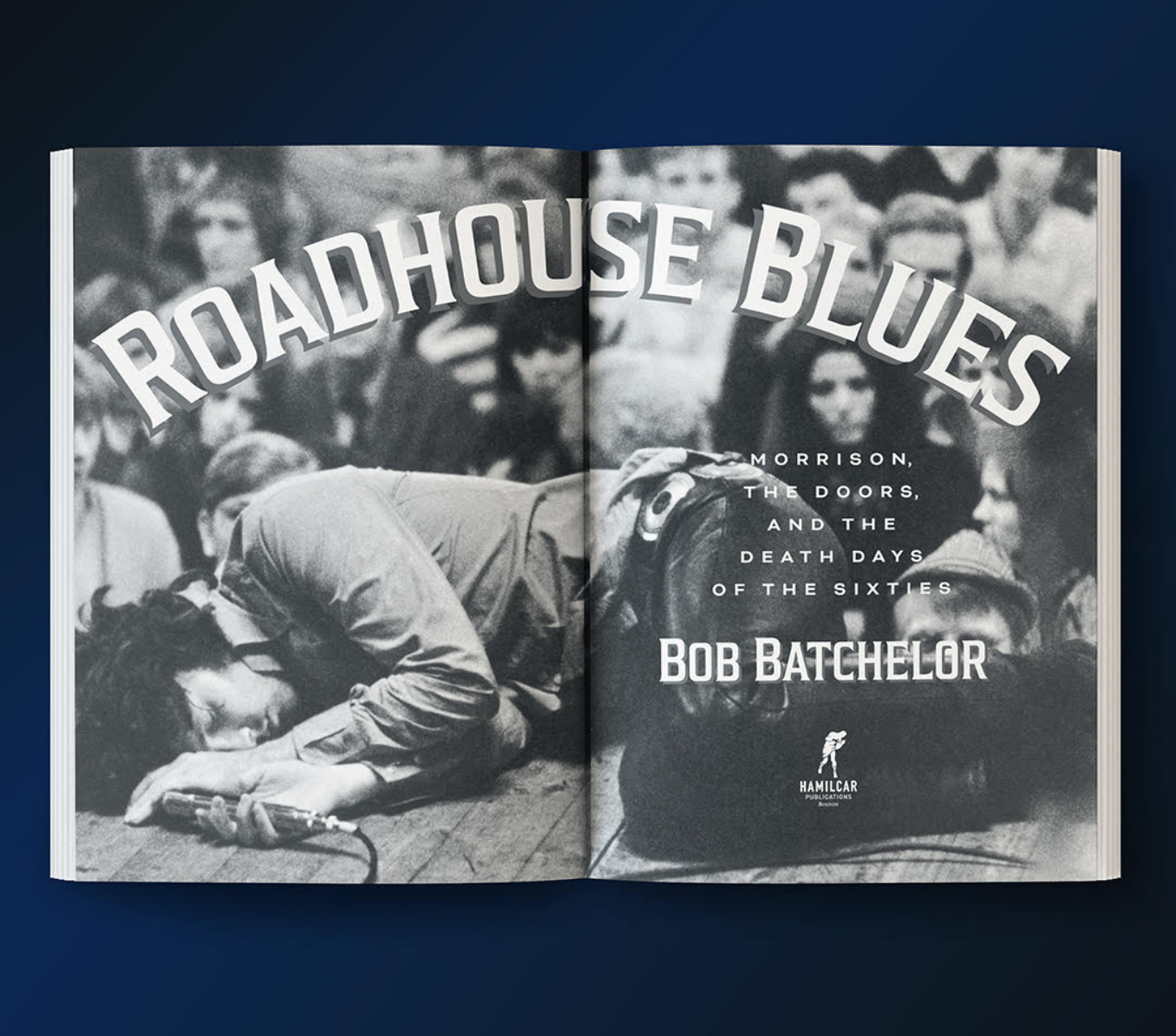

Photo by Aneta Pawlik on Unsplash

If you’re just beginning your book journey, here are five essential tips drawn from my own experience:

1. Establish a Writing Rhythm That Works for You

Life is demanding. Your writing process should complement—not fight—your daily responsibilities. Consistency, not volume, builds momentum. Even 20 minutes a day adds up.

2. Start with a Strong Outline

Before I write a word, I create a detailed Table of Contents. For nonfiction, this map is critical. Think deeply about how you plan to open each chapter—those first lines carry a lot of weight.

3. Don’t Believe in Writer’s Block

Writing is work. Work requires discipline. When I feel creative fatigue, I don’t panic. Instead, I switch gears. Reading for pleasure, often on my Kindle, lets me absorb ideas passively and recharges my creative energy.

4. Let Your Curiosity Drive the Research

Even after I have started writing, I keep researching. Every new detail might unlock a better sentence, a sharper insight, or a deeper connection. Curiosity is your most sustainable writing fuel.

5. Experiment with Storytelling Techniques

In The Bourbon King, I explored a postmodern style in one chapter to capture the extravagance of George Remus’ legendary New Year’s Eve party. Creative nonfiction allows room for innovation…even in history-heavy narratives.

The Bourbon King by cultural historian Bob Batchelor

Most importantly, allow yourself time to grow. The voice you find in your first book might surprise you. It should.

To support your own writing journey, keep reading widely and learning from others. Books like The Bourbon King or Stan Lee: A Life can be models—narrative-driven nonfiction that brings culture, history, and people to vivid life. You can find these and other inspiring reads on Amazon and even save a bit with these offers.

Stan Lee: A Life by Bob Batchelor

So what are you waiting for? Open that document. Name your project.

Take the first step. Your book is waiting.

I use Amazon affiliate links on this site—mainly links to books or other cool things. And if you buy via my links, it supports the site with no extra cost to you. This is a contributed post and may contain affiliate links. I was compensated for this post, but reviewed it and regard the article as a natural fit for my readers.